Hill Country

CURRENT ISSUES

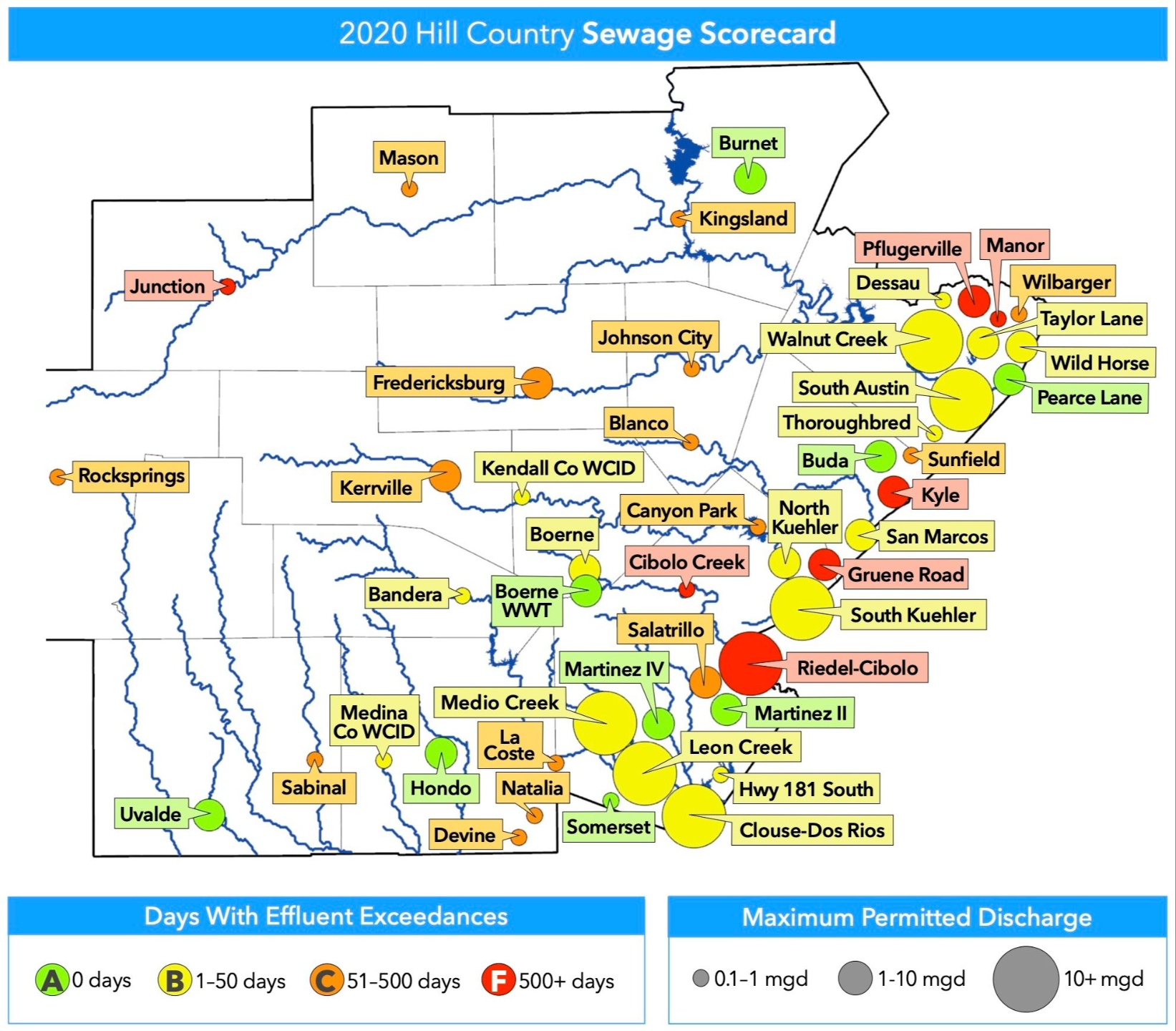

Wastewater Conservation Coalition • Hill Country Sewage Scorecard

The Hill County is arguably the most popular part of Texas, but the natural features that contribute to its unique beauty are in danger of being lost to overdevelopment. The area's spring-fed and sparkling clear streams attract millions of visitors from across the state each year for swimming, fishing, and tubing, but these rivers and creeks can quickly become polluted by poorly treated wastewater and dirty stormwater runoff. The region's rocky soil can hold more moisture and support more vegetation than most people realize, but these benefits are lost when bulldozers scrape the land bare for new construction. Preserving the natural beauty of this region is a priority not just for the people who live here, but also for the many Texans who love it precisely because it's so different from the rest of our state.

WHAT WE DO: Save Texas Streams Board Member Sarah Larocca (center left) and Save Texas Streams' previous Executive Director Angela Richter (center right) collected signatures for the No Dumping Sewage petition, which called for an end to new wastewater discharge permits in the Edwards Aquifer Contributing Zone, at our Brews & Bluegrass event in 2018.

Wastewater Conservation Coalition

The Wastewater Conservation Coalition (WCC) includes 15 member organizations and affiliated individuals working together to keep Hill Country streams and aquifers free of pollution from wastewater by promoting its reuse. The coalition was originally founded in 2017 as No Dripping Sewage in order to provide education about a wastewater discharge permit application by the city of Dripping Springs. The group's founding members — Save Texas Streams, Clean Water Action, Greater Edwards Aquifer Alliance, and the Wimberley Valley Watershed Association — continued the coalition as No Dumping Sewage and expanded its scope to include all of the Hill County. Members voted to change the name again in 2023 to the Wastewater Conservation Coalition.

WCC members meet monthly to discuss pending wastewater permit applications in each organization's area of operation. Because of these ongoing conversations, WCC participants are able to share notes and identify when TCEQ includes different requirements in similar permits. In 2023, for example, the agency's staff proposed very different phosphorus limits for discharge permits on two pristine streams — 0.15 milligrams per liter for Liberty Hill's permit on the South San Gabriel River, and 0.5 milligrams for Gram Vikras's permit on Hondo Creek — even though both streams had almost identically low levels of naturally occurring phosphorus. The information that WCC members share with each other has enabled us to hold TCEQ accountable on inconsistencies such as these.

WCC Permit Tracker: This chart highlights the discrepancies in the requirements that TCEQ has included in similar wastewater permits. Key: (C)BOD = (Carbonaceous) Biochemical Oxygen Demand; TSS = Total Suspended Solids; NH3 = Ammonia Nitrogen; TP = Total Phosphorus. All measurements are in milligrams per liter.

WWC member organizations include the Cibolo Center for Conservation; Clean Water Action; Devils River Conservancy; Greater Edwards Aquifer Alliance (GEAA); Hill Country Alliance; Llano River Watershed Alliance; National Wildlife Federation; Pedernales River Alliance; San Marcos River Foundation (SMRF); Save Our Springs Alliance (SOS); Save Texas Streams; Texas Real Estate Advocacy & Defense Coalition (TREAD); Texas Rivers Protection Association; Trinity Edwards Springs Protection Association (TESPA); and The Watershed Association. Save Texas Streams has served as facilitator for the coalition since 2020.

Hill Country Sewage Scorecard

The Hill Country Sewage Scorecard, published by Save Texas Streams in 2020, remains the only study to evaluate the performance of wastewater treatment facilities throughout the region. For this report we examined pollutant monitoring data that was self-reported by the 48 municipal sewage treatment plants with discharge permits in the region’s 17 counties. We found that during the during the study period, 39 facilities exceeded at least one of the pollutant limits set by TCEQ in their operating permits. In other words, 81 percent of Hill Country sewage plants dumped something into a stream that wasn’t allowed by their permit at least once since 2017.

The most common exceedances were for oxygen demand and suspended solids (both of which can harm aquatic life), and E. coli bacteria (which can harm people). The key measurement used for this report was the total number of days with reported pollutant exceedances. During the study period, 6 plants exceeded at least one permit limit on 1-50 days; 15 plants, on 51-500 days; and 6 plants, on more than 500 days. Only 9 plants (out of 48 municipal wastewater treatment facilities included in the study) complied with all of their permit limits. Equally worrying, TCEQ failed to take action against most of the noncompliant plants. Of the 39 facilities that reported at least one permit exceedance, TCEQ issued a formal enforcement action and monetary penalty against only 11, or less than one-third.

Any wastewater facility with a discharge permit must regularly test the water quality of its treated sewage and report these results to TCEQ and the EPA. Save Texas Streams used this data to calculate the grades in our Hill Country Sewage Scorecard.

The enforcement of wastewater discharge permits starts with the treatment plants themselves, which are required to regularly test the water quality of their treated sewage. Texas plants must include the test results in the monthly discharge monitoring reports that they have to file with the TCEQ, which forwards the data to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA then makes this information available to the public on its Enforcement and Compliance History Online (ECHO) website. For our study, Save Texas Streams analyzed the data posted on ECHO for all of the municipal sewage plants in the Hill Country.