Aquifer Protection

Save Texas Streams works to ensure our aquifers are clean and not over-drawn, so that we have plentiful water supply for generations to come.

What is an Aquifer?

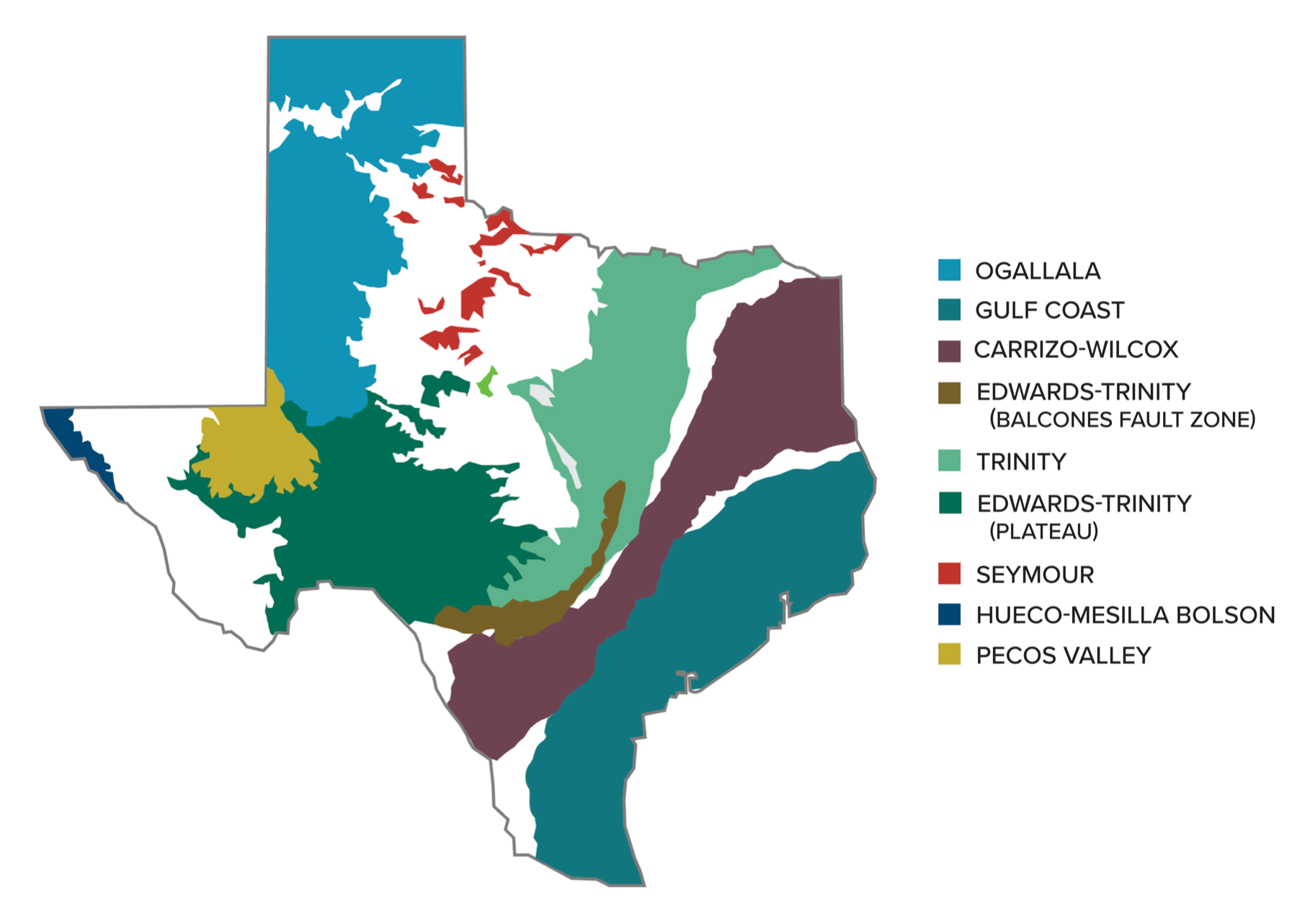

Aquifers supply one-third of the water that Texans outside the Panhandle use. (This statistic excludes the state's largest aquifer, the Ogallala, because it's used almost exclusively for agricultural irrigation in the Panhandle.) But despite their importance, few Texans understand what aquifers are. While they're sometimes described as underground reservoirs , that can give the impression that they're like a subterranean river or lake, which isn't the case.

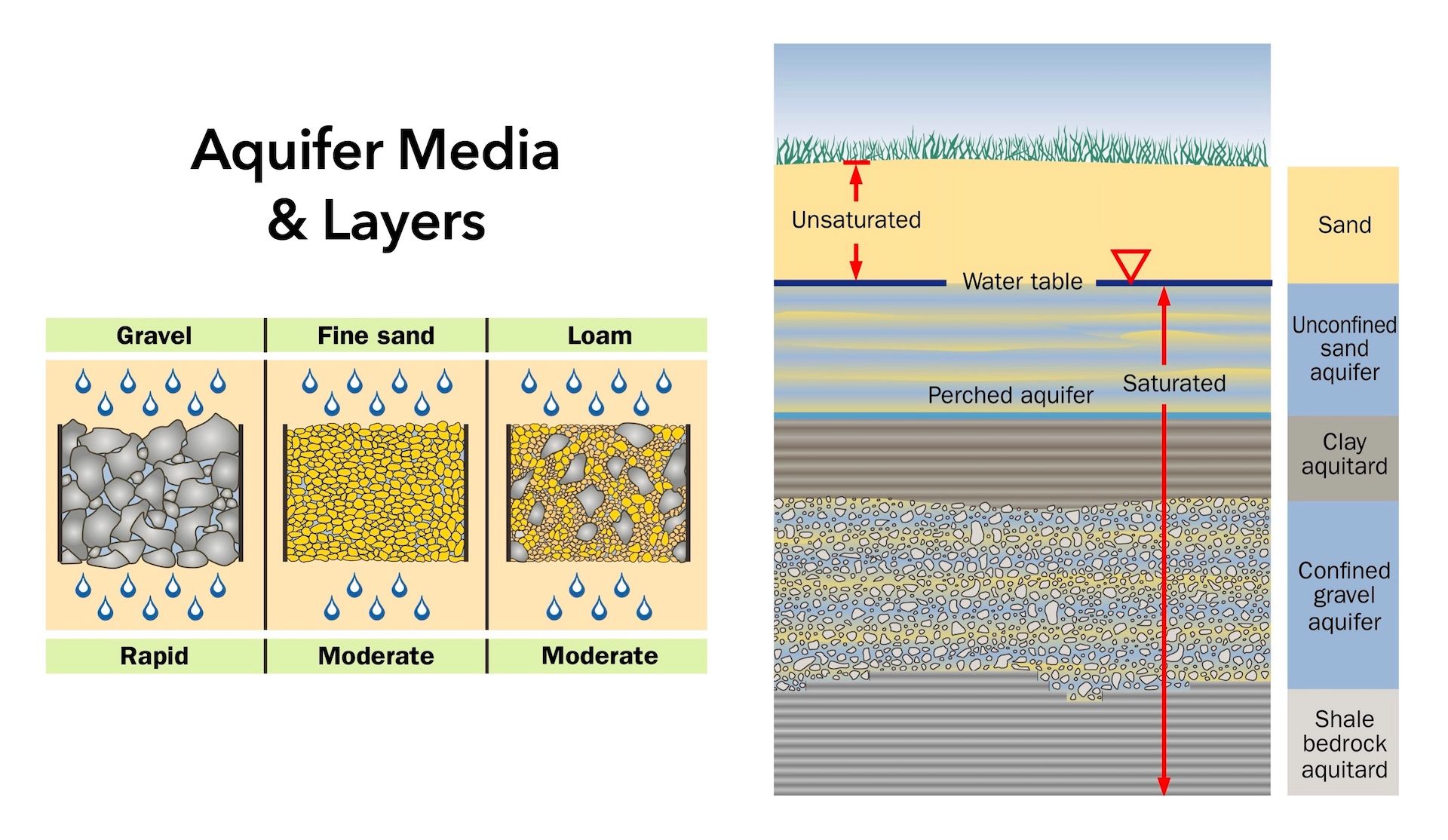

A more accurate way to describe an aquifer is as an underground layer of wet sand or wet gravel. (The Edwards Aquifer is an exception, which we'll explain in a moment.) Water that seeps down from the surface is contained in the space between individual particles of sand or gravel. While these spaces are tiny, they can collectively hold a huge amount of water in the largest aquifers, which extend underground for thousands of square miles. In Texas, the Ogallala Aquifer lies under 49 counties; the Trinity, under 61; and the Carrizo Wilcox, under 66.

The aquifers that are important for our state's water supply are confined aquifers. That means that water stays in an aquifer because this buried layers of sand or gravel is confined on its top, bottom, and sides by other more dense layers of clay or rock that restrict the flow of water. Because of this confinement, the aquifer is like a vessel that can fill up and create pressure. Water is forced out of the aquifer by this pressure through escape valves that we know as natural springs.

The process by which water seeps into an aquifer is called recharging. Water doesn't seep into the aquifer over its entirety, but only in a portion called the recharge zone or the outcrop, where the aquifer is at the surface or closer to it. The amount of time that it takes water to travel from the surface into the aquifer is called the recharge rate. For most aquifers in Texas, this process is extremely slow, and is measured in decades, centuries, or even millenia.

One of the best-known aquifers in the state, the Edwards, is a exception because water is stored in its vast underground layer of karst limestone. Karst means that the rock contains an immense number of conduits and spaces that range in size from almost invisible fractures to massive caves. Because the space that holds water in a karst aquifer is much larger than in a clay or gravel aquifer, a karst aquifer can also be recharged more quickly, and water travels through it more quickly.

Aquifers are extremely important in Texas because they help supplement our surface water, but they can also be overused. In most parts of the state, we're pumping water out of aquifers at a faster rate than they can recharge. In fact, the Ogallala Aquifer — which lies not just under the Texas Panhandle, but also most fo the Great Plains — is expected to become unusable for agriculture in a few decades. Overpumping is a problem even if not all of the water in an aquifer is withdrawn. Pumping water out of an aquifer also reduces the pressure within it, and if the pressure gets too low, surface wells will become unusable.