Salado Creek

12 new permits =

8 million gallons of wastewater per day

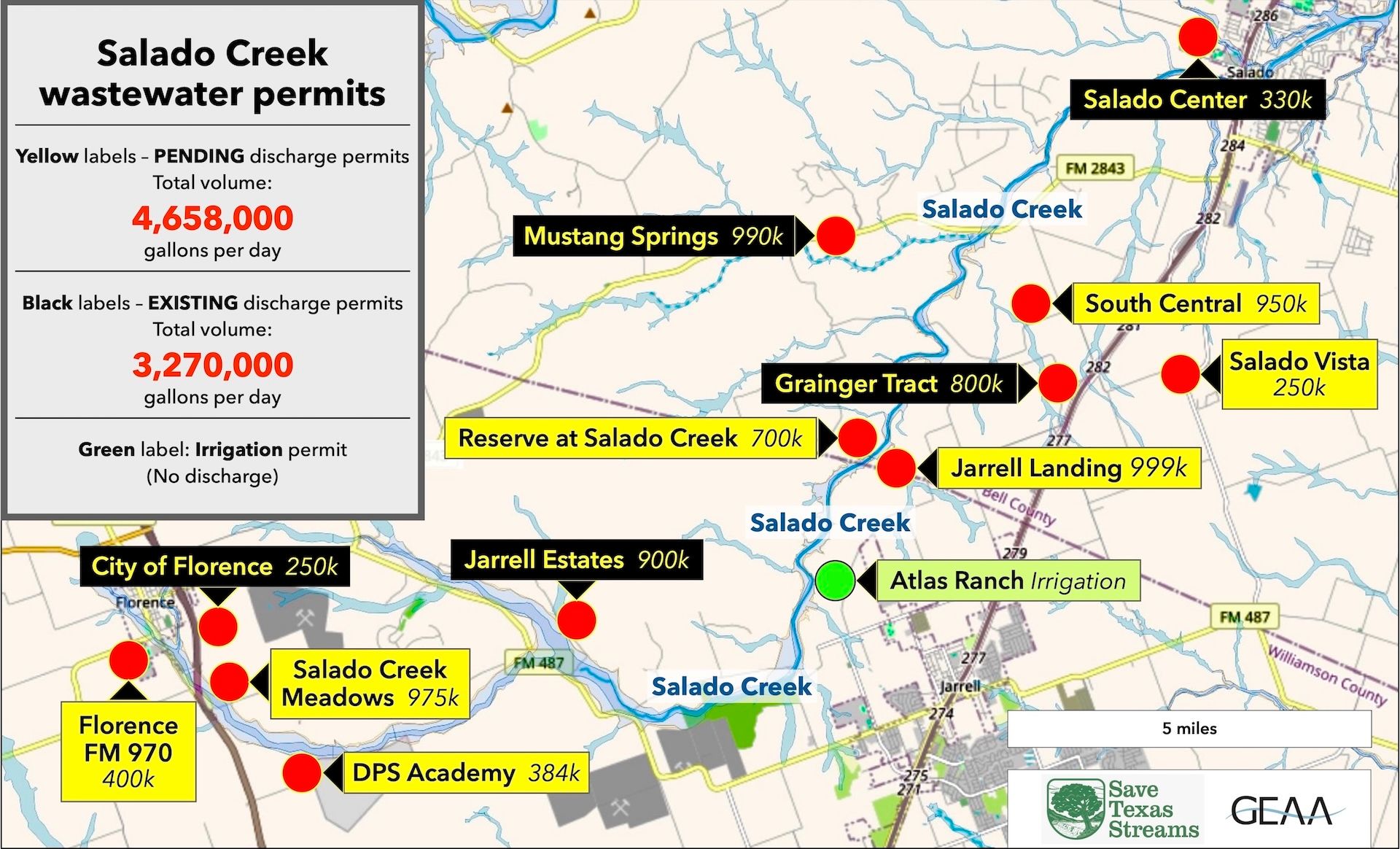

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality is currently reviewing or has already approved permits for 12 facilities that could discharge 8 million gallons of treated wastewater (aka sewage) into Salado Creek, a pristine stream that flows over the Edward Aquifer Recharge Zone in Bell and Williamson Counties.

What can you do?

Attend the next Salado Creek Community Meeting:

March 3, Tuesday, 6:30pm, at Salado Museum

Speaker: Jeff Back from Baylor University

Submit comments on the draft wastewater permit for Salado Vista:

Go to: TCEQ Online Comment Form

Enter permit number: WQ0015664002

Deadline: February 23

Suggested comments below

Resources

STS letter to TCEQ on Reserve At Salado Creek permit – 01.27.26

This letter describes in detail the problems with the draft permit for The Reserve. Most of the other permits on Salado Creek share these same problems.

STS meeting presentation on all Salado Creek permits – 01.19.26

This presentation includes maps, photos, and charts to explain the problems with the Salado Creek permits.

STS presentation on the Contested Case process for TCEQ Permits – 02.03.26

This presentation explains how to file a contested case request on a TCEQ permit and what's required for it.

How to find permit information and submit permit comments on TCEQ's website:

Save Texas Streams TCEQ Permit Guide

Questions? Contact us at:

[email protected]

Salado Vista’s permit problems

Save Texas Streams urges you to submit comments to TCEQ on the Salado Vista draft permit by February 23. Go to the TCEQ online comment form at https://www14.tceq.texas.gov/epic/eComment/ and enter permit number WQ0015664002. These are the key problems with this permit:

Salado Vista is a proposed subdivision that would be located on Hackberry Road east of I-35 and west of FM 2115. Louis A. Tsakiris Family Partnership, Ltd., of Houston has applied to TCEQ for a TPDES permit that would allow Salado Vista's treatment facility to discharge 250,000 gallons of wastewater every day.

Problem: TCEQ's draft permit for Salado Vista says that the discharged wastewater will flow east and south in a roadside ditch along Hackberry Road and drain into Darrs Creek, which flows into the Little River. But it will be impossible for the wastewater to flow this way, since Hackberry Road has two up-and-down elevation changes before reaching Darrs Creek, as shown on topographic maps from TCEQ and the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department.

Problem: Salado Vista’s discharged wastewater is more likely to flow into Salado Creek since the location for its treatment plant, as described in TCEQ’s draft permit, is next to a drainage channel that flows north to Salado Creek.

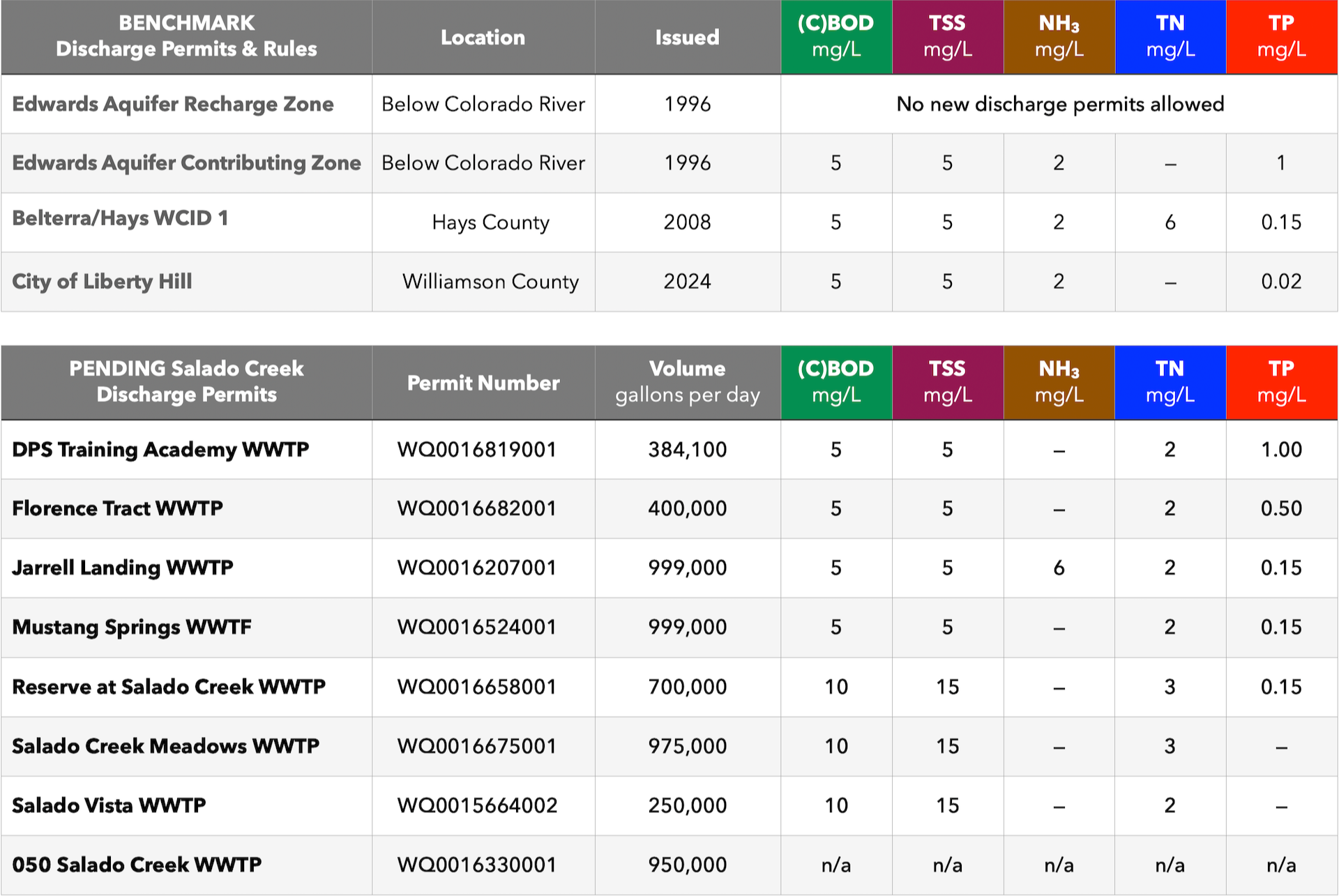

Problem: TCEQ’s draft permit for Salado Vista has the worst permit limits of all of the 12 new and pending discharge permits on Salado Creek. The Salado Vista permit has the highest limits for BOD (10 milligrams per liter) and TSS (15 milligrams per liter). And it has no limit at all for Total Phosphorus, which is the key ingredient in treated wastewater that’s caused massive algae blooms elsewhere.

Problem: TCEQ’s staff apparently included worse limits in the Salado Vista draft permit because they did not examine the applicant’s claim that its wastewater will be discharged into Darrs Creek. Because this wastewater is more likely to end up in Salado Creek, TCEQ must set stricter limits for Salado Vista.

Problem: Salado Creek is a pristine stream that will be very susceptible to high amounts of additional phosphorus from discharged wastewater. For this reason, the permit for Salado Vista — and for all discharge permits on Salado Creek — should contain a Total Phosphorus limit of 20 micrograms per liter. TCEQ determined in 2024 that this was the appropriate phosphorus limit for Liberty Hill's discharge facility on the South San Gabriel River, which is also a low-phosphorus pristine stream like Salado Creek.

Problem: Because Salado Vista’s wastewater will likely flow into Salado Creek TCEQ must include it when calculating the cumulative impact of all 12 new and pending discharge permits on the creek.

At risk: a pristine stream & the Edwards Aquifer

TCEQ has already approved 5 of the new wastewater discharge permits, and it’s currently reviewing the remaining 7. Salado Creek is an exceptionally pristine and spring-fed stream, and it will not be able to handle 8 million gallons of treated wastewater per day. Because the creek has little to no flow during dry months, it will essentially be transformed into a sewage drainage ditch. The 12 approved and pending permits on Salado Creek represent one of the highest concentrations of new wastewater permits anywhere in Texas.

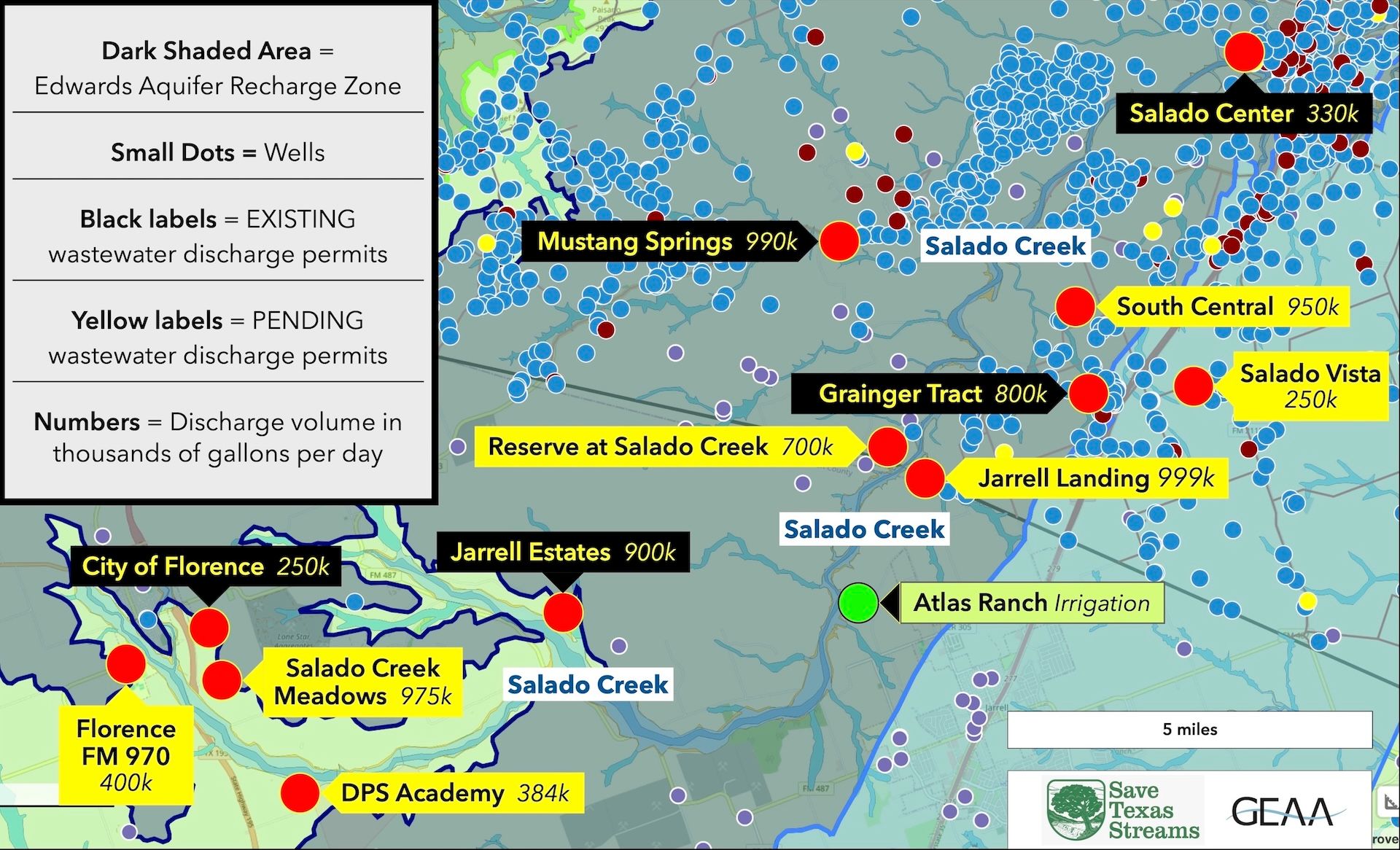

Several of the pending wastewater discharge permits are also in the Recharge Zone of the Edwards Aquifer. In 1996, TCEQ banned new wastewater permits in the Edwards Recharge Zone south of the Colorado River. If that ban had included the full extent of the Recharge Zone north of the Colorado River, most of the current discharge permit applications couldn’t have been filed. Also, while TCEQ still issues TLAP irrigation permits in the southern extent of the Edwards Recharge Zone, it only approves one type of dispersal method — surface spray irrigation — but not the other — subsurface drip irrigation. TCEQ's rationale for not approving subsurface drip over the Recharge Zone is the same reason it doesn't issue wastewater discharge permits in this area — in order to protect the water supply for millions of Texans who get their water from wells drilled in the Edwards Aquifer.

The South San Gabriel Warning

The problems with the pending permits on Salado Creek would be exacerbated by the inadequate treatment requirements that TCEQ has drafted for them. In particular, these pending permits would have very high or no limits on the amount of phosphorus that could remain in wastewater after it’s been treated and before it’s discharged. Phosphorus is a plant fertilizer, and adding more of it to pristine streams with very low amounts of naturally occurring phosphorus will fertilize the growth of excessive algae.

This has already happened in Williamson County west of Georgetown. The South San Gabriel River, which is also a pristine stream with little phosphorus, has been blanketed with excess algae for several miles below the point where Liberty Hill discharges its treated wastewater, which contains higher levels of phosphorus (see photo montage below). The draft permits that TCEQ has written for the pending applications on Salado Creek would allow treated wastewater to be discharged with 15 to 100 times more phosphorus than what’s in the creek. And while Liberty Hill was only discharging around 1 million gallons of treated wastewater into the South San Gabriel, the 11 existing and pending permits on Salado Creek could potentially discharge up to 8 million gallons per day.

The South San Gabriel River (above), which is located 20 miles south of Salado Creek, has been plagued with excessive algae caused by treated wastewater for more than a decade. This montage shows consecutive segments of the South San Gabriel as seen in a drone video shot in 2020 by Ryan King, a nationally renowned water quality scientist at Baylor University. These images showed how excessive algae grew on the South San Gabriel downstream from the city of Liberty Hill's wastewater discharge outlet, located at the midpoint of the photo at far left.

Comparing permit limits

Carbonaceous Biochemical Oxygen Demand (CBOD) — This is an indirect measure of how well wastewater has been treated. A high CBOD level means that the discharged wastewater will deplete a higher amount of dissolved oxygen in a stream, which can lead to fish kills.

Total Suspended Solids (TSS) — This is also an indirect measure of how well wastewater has been treated.

Ammonia Nitrogen (NH3) and Total Nitrogen (TN) — Ammonia in discharged wastewater can break down into harmful nitrites and nitrates.

Total Phosphorus (TP) — Because phosphorus fertilizes the growth of plants, a high TP level in discharged wastewater can fertilize the growth of excessive algae in streams with very low levels of naturally occurring phosphorus, such as Salado Creek.

* Permit information compiled by Greater Edwards Aquifer Alliance (GEAA)