Tapping into Central Texas Aquifers

Did you know that 53.5% of Texas’s drinking water comes from aquifers? There are 4 major aquifers in Central Texas, all of which are essential to sustaining our municipalities, livestock, agricultural irrigation, and diverse wildlife. In this article, SBCA aims to dig deep into our region’s aquifer systems, uncovering the topography, hydrogeology, and geography that make them each so distinctive, while also highlighting the hydraulic connections that exist between them. We hope you enjoy this deep dive into Central Texas aquifers!

Aquifers are essentially underground water storage units that are refilled, or recharged, when surface water percolates through layers of porous rock. Any surface area through which water infiltrates and replenishes an aquifer is commonly referred to as a recharge zone. Travis and Hays country residents are likely familiar with road signs that read, “Entering Edwards Aquifer environmentally sensitive Recharge Zone.” These signs were installed with the intention of raising awareness for the aquifer’s water quality and preventing the contamination of groundwater from surface activities. Conversely, an aquifer contributing zone is any area where surface water (streams and rivers) will eventually flow into a recharge zone and contribute to an aquifer. Due to Central Texas’s varied geology, the depth of the aquifers beneath our feet ranges from just a few meters below the surface to several hundred meters deep. Aquifer depth refers to the distance between the ground surface and the base of the aquifer, while saturated thickness is the vertical distance from the top of the aquifer’s water table to the base of the aquifer.

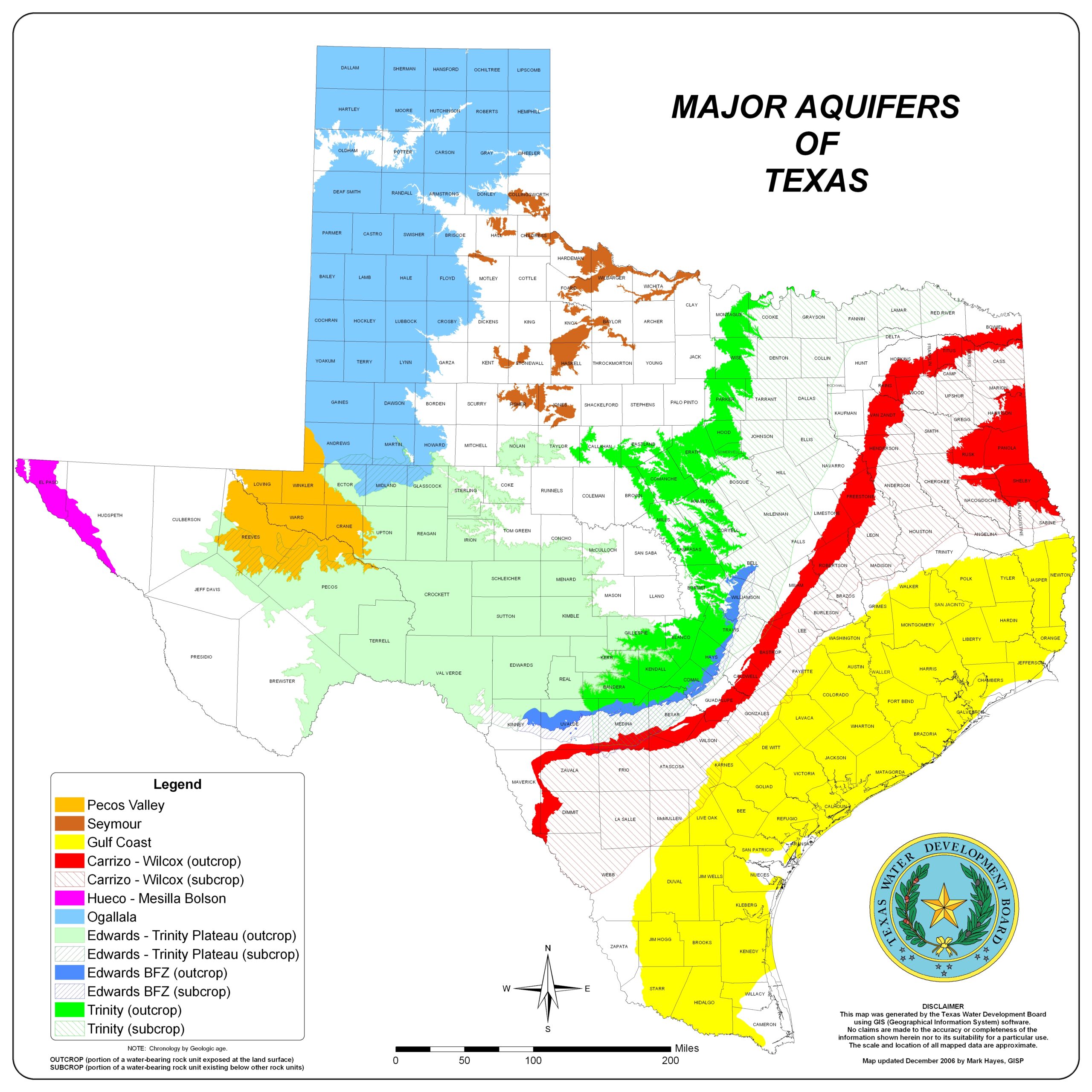

Most people tend to imagine aquifers as still, stagnant underground pools, but this is far from the case. The water under our feet is very much active, constantly flowing as part of the greater hydrological system. Aquifer water seeps through cracks and fissures, follows currents, and can even undergo immense pressure, propelling it back up to the surface through artesian springs. Aquifers with artesian springs are referred to as confined, because the water within them is trapped between two confining layers of impermeable rock. Artesian springs occur when confined aquifers experience high-pressure conditions, causing the water to shoot up through any accessible channel. This is how Barton Springs and many other springs that feed Texas Hill Country rivers formed! Aquifers that are not sandwiched between layers of impermeable rock are known as unconfined aquifers and do not experience these same high-pressure conditions. The map below delineates Texas’s 9 major aquifers and distinguishes their outcrops from their subcrops. Outcropsare the areas of aquifer exposed to the surface and are generally unconfined, while subcrops are areas of aquifer buried beneath other formations and typically signify confined conditions.

Major Aquifers of Texas (Mark Hayes & Texas Water Development Board, 2006)