Say Hello to Our Newest Water Laws

Because Texas doesn’t have a legislature that meets on an annual schedule like normal states, we’re now in the middle of a 30-day special session that started on July 21. And because there’s a bit of controversy going on at the Capitol, Governor Abbott will likely call a second special session after this one ends. (In 2023, he ordered legislators back to Austin for 4 special sessions). Still, this is a good time to look at the water bills that were passed in the 140-day regular session that ended on June 2 and that have since been enacted into law.

This classic “Schoolhouse Rocks” video explained how bills become laws.

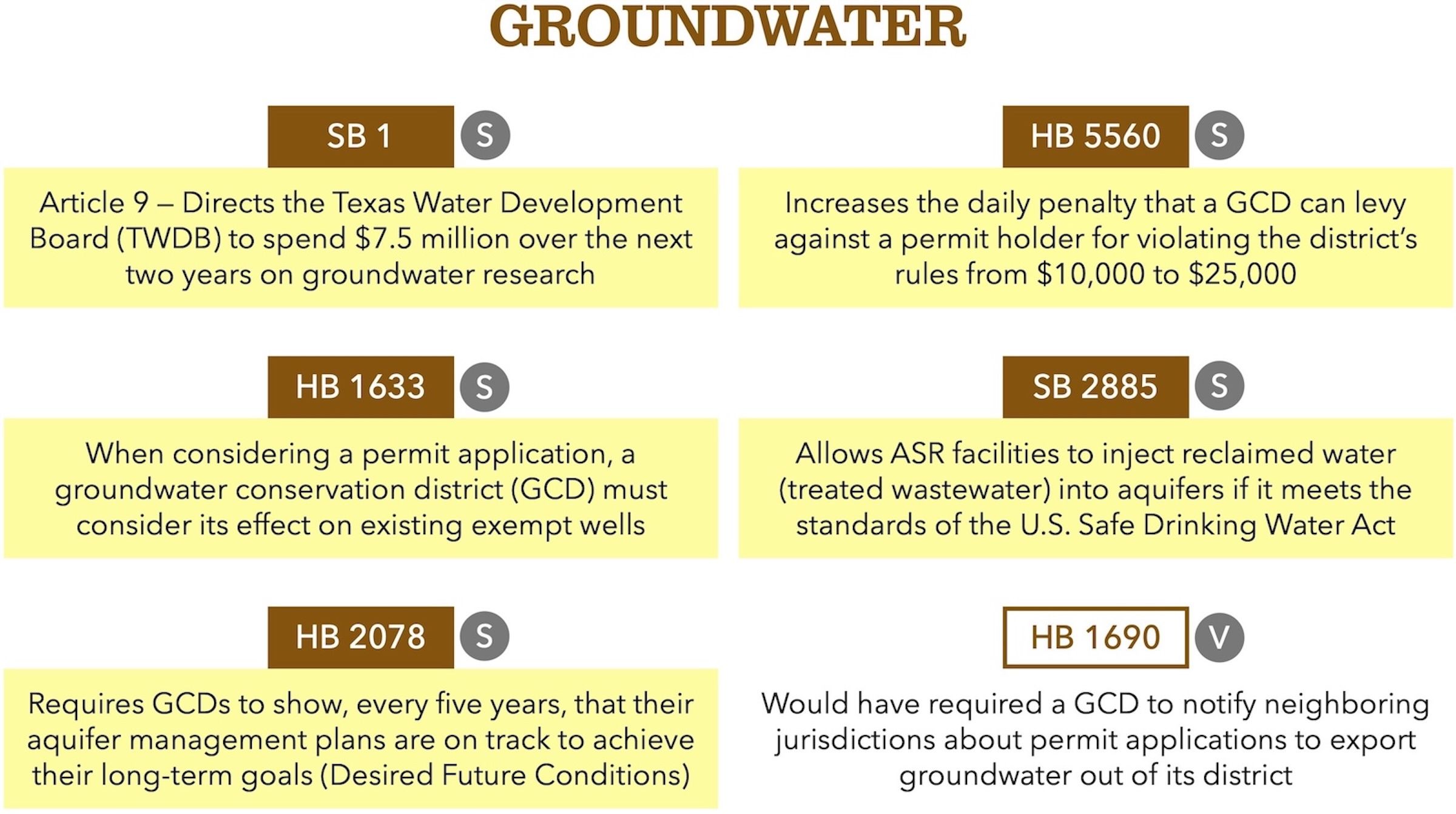

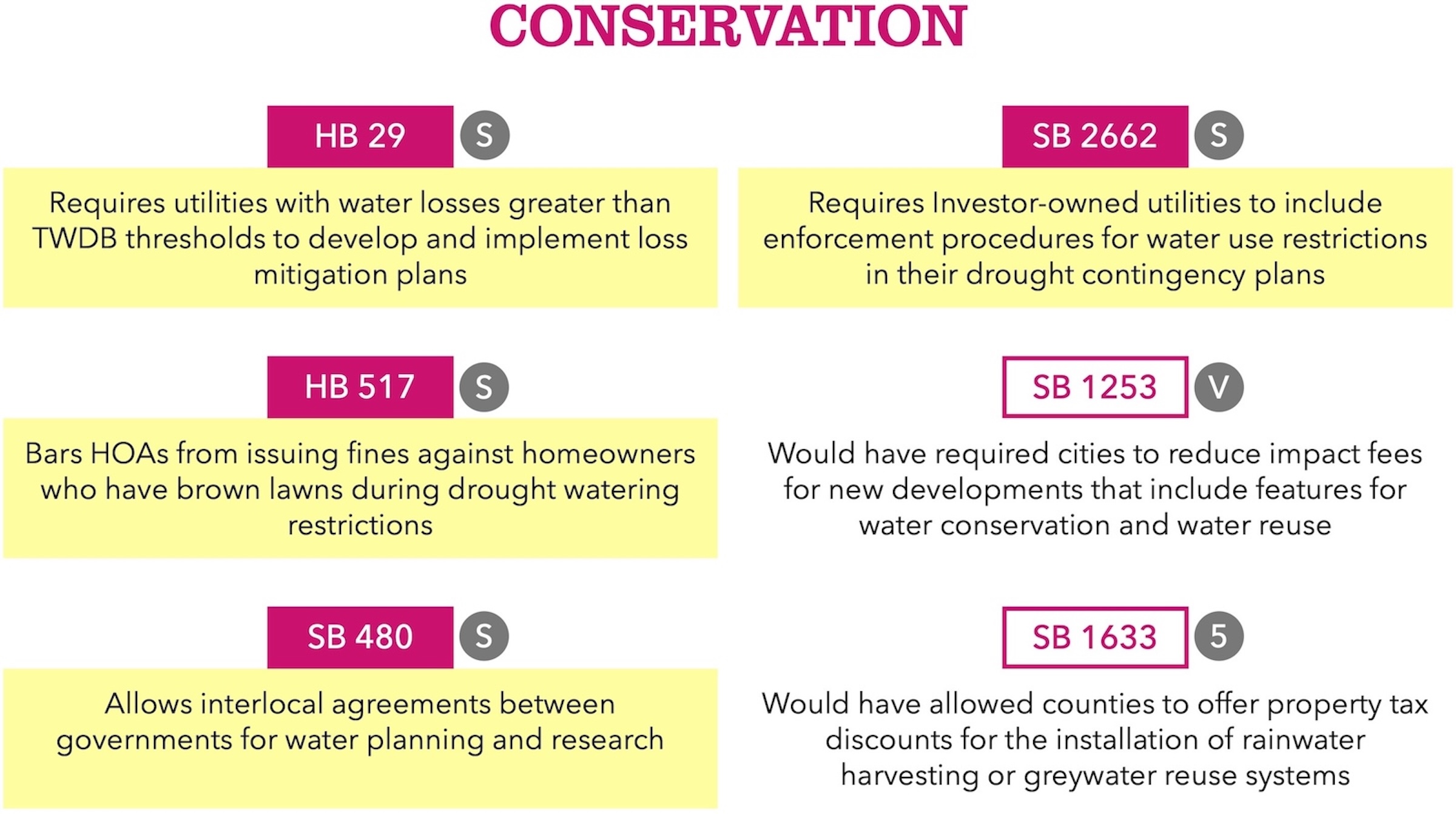

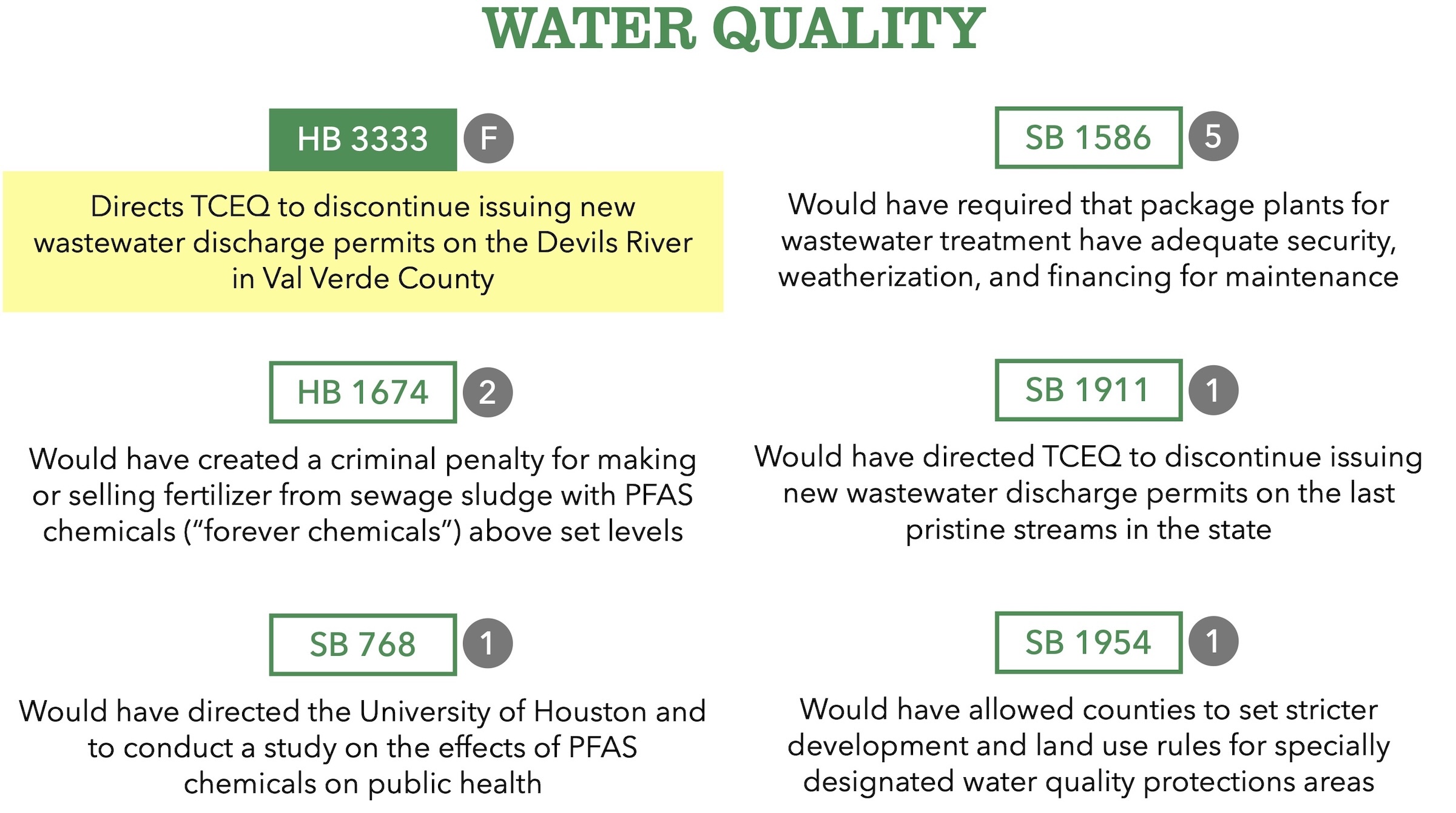

All of the new laws listed below (indicated by colored blocks) will go into effect on September 1 unless otherwise noted. We’ve also listed some good bills that should have become law but didn’t (indicated by white blocks). In the gray circle to the right of each bill number, we’ve indicated the highest stage reached by each piece of legislation. The governor has the option to Sign a bill into law, Veto it, or to not take any action on it by his deadline to do so, in which case it’s automatically Filed as a new law. For bills that never even made it to the governor’s desk, we’ve indicated the highest stage in the legislative process that they reached (see the key at the end for an explanation of the numbers). Keep scrolling to read about new legislation for Groundwater, Conservation, and Water Quality. You can also read this Legislative Report and our previous one at:

SaveBartonCreek.org/Legislature-2025

Groundwater is the term used by policymakers to refer to what most people would call underground water, because it can only be accessed if you pump it out of a well. Groundwater comes from surface water that seeps into underground reservoirs called aquifers, which usually contain the water in layers of sand or gravel. Not every location in Texas is located over an aquifer. According to this Texas Tribune story, 53.5% of our state’s water supply comes from groundwater in aquifers, 42.8% comes from surface water in rivers and lakes, and 3.7% comes from water reuse.

Texas has 98 local Groundwater Conservation Districts (GCDs), which issue both drilling permits and pumping permits. The latter are technically called production permits, since they allow a specified amount of water to be produced from a well. Conservation in the GCDs’ name means that they’re supposed to conserve their local groundwater supply, so that there’s enough for everyone. A majority of the state’s county’s have GCDs; in counties without a GCD, there are no regulations on groundwater drilling and pumping. Wells can be either Registered with a GCD or Exempt, meaning that they usually aren’t covered by a GCD’s regulations. The Texas Water Development Board (TWDB) is a state agency that provides planning, research, and funding assistance to Groundwater Conservation Districts.

SB 1 — Article 9 of this law, which contains the state’s budget, directs TWDB to spend $7.5 million over the next two years on groundwater science, research, and innovation. This new funding will be crucial since many GCDs don’t know exactly how much water is available in their aquifer, which means that they don’t know how many permits they can issue, and for how much volume. Knowing how much water can be pumped out of an aquifer is essential for a GCD so that it can determine whether it’s on track — or not — to meet its Desired Future Condition (see HB 2078 below).

HB 1633 — This new law requires Groundwater Conservation Districts to consider the impact of a new permit application on not just existing Registered wells, but also on Exempt wells (this usually includes single-household and small agricultural wells). According to the bill’s author, GCDs in some counties have been ignoring the impact of new permits on Exempt wells.

SB 2885 — We’re not just limited to pumping out the water that nature has put into an aquifer. It’s also possible for us to pump water into an aquifer and then pump it out later, using Aquifer Storage & Recovery (ASR) facilities. The water that’s pumped into a well will generally be excess stormwater collected during a heavy rainfall, but El Paso has been a pioneer in pumping treated wastewater into an aquifer. (Treated wastewater that’s discharged into rivers and lakes is already supplementing our drinking water sources across Texas.) SB 2885 clarifies that as long as wastewater has been treated to drinking water standards, ASR facilities can pump it into an aquifer.

HB 2078 — All Groundwater Conservation Districts are required to set a long-range planning target called the Desired Future Condition (DFC). For example, a district might say, “We don’t want the water level in our aquifer to go down by more than 200 feet over the next 50 years.” HB 2078 requires GCDs to show, every five years, that their current aquifer management policies are on track to meet their Desired Future Condition.

HB 5560 — Groundwater Conservation Districts are already able to issue fines against permit holders that violate the district’s rules. This new law raises the maximum fine from $10,000 per day, to $25,000 for every day that the permit holder doesn’t follow the GCD’s requirements.

HB 1690 — The process of moving water from one jurisdiction to another is called exporting. For surface water, this can mean building a pipeline to move water from one river basin to another. For groundwater, this can mean pumping water out of one GCD and piping it to another. Before well owners can do this, they must apply for an export permitfrom the GCD. HB 1690 would have required a GCD to notify neighboring jurisdictions when it was considering an export permit application. Governor Abbott vetoed the bill, stating that it “would increase the regulatory hurdles to convey water resources.” However, groundwater exporting has become increasingly controversial in Texas (you can read more here, here, and here), so it’s likely that this proposal will come up again.

While other strategies try to increase our supply of water, conservation aims to decrease our demand for water. It’s generally easier to build conservation features into new construction rather than add them to existing developments.

HB 29 — If you have an older home, you already know that pipes and faucets can leak. The same is true for large-scale water infrastructure in municipal utilities, which can have equally large-scale leaks. According to this excellent Texas Living Waters Project report, the amount of water that’s lost statewide each year would be enough to meet the combined annual water needs of Austin, Fort Worth, El Paso, Laredo, and Lubbock. TWDB already sets levels for the amount of acceptable water loss by municipal utilities. HB 29 says that if a utility exceeds this threshold, it must create and implement a mitigation plan to reduce its water loss.

HB 517 — Have there really been homeowners associations (HOAs) that have been stupid enough to fine residents for having brown lawns simply because they were following their utility’s watering restrictions during droughts? Apparently there have been. This new law, which went into effect on May 29, tells HOAs to stop doing that.

SB 480 — This small but helpful law clarifies that local governments can engage in joint water planning and research with other governmental entities.

SB 2662 — While most people get their water from a public nonprofit utility, some are served by for-profit corporations, referred to as Investor-Owned Utilities (IOUs). And while public utilities have long been required to have drought contingency plans to reduce consumption when water is scarce, corporate utilities have not. Under this new law, corporate utilities must now have drought contingency plans that include mandatory water use restrictions, as well as procedures for dealing with users who don’t comply with these restrictions. SB 2662 went into effect on May 30.

SB 1253 — This bill would have incentivized the inclusion of water conservation features in new developments by requiring cities to reduce impact fees for these developments. As we explained in our previous newsletter, Governor Abbott vetoed this bill because it would have also expanded the authority of the Hays Trinity Groundwater Conservation District. You can read more in this Texas Monthly article, “Why the Best Chance to Save Jacob’s Well Drained Away.”

SB 1633 — This was another great bill that would have allowed counties to offer property tax discounts for the installation of onsite rain harvesting or greywater reuse systems. (Greywater is the wastewater from bathroom drains and washing machines.) Versions of this bill have been introduced in several previous sessions. This time, SB 1633 was passed by the Senate but died in the House.

Water Quality generally refers to the amount of pollutants that are present in natural water features like rivers, lakes, and aquifers. (It doesn’t refer to drinking water quality, which is a separate topic in laws and regulations.) Improving water quality means limiting or reducingthe amount of pollutants in natural waters.

HB 3333 — This new law directs the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) to stop issuing new permits that would allow treated domestic wastewater (aka sewage) to be discharged into the Devils River north of Del Rio. TCEQ previously discontinued new wastewater discharge permits in a 10-mile buffer zone around the Highland Lakes in 1986, and over the Edwards Aquifer Recharge Zone in 1996. HB 3333 was spearheaded by the Devils River Conservancy, which previously joined SBCA in filing the Pristine Streams Petition with TCEQ in 2022 (see below).

HB 1674 — You may have read recent articles about the potential dangers of PFAS chemicals in fertilizers that are made as a byproduct of the wastewater treatment process. The letters refer to tens of thousands of chemicals that share similar and very complex molecular bonds. This is why they’re also called “forever chemicals,” since they take a really long time to break down and decay. In the wastewater treatment process, solids settle to the bottom of the treatment tanks. When these biosolids are removed, they’re often turned into fertilizer, since they have high levels of phosphorus and nitrogen (which are two of the three ingredients in many commonly used fertilizers). But because trace amounts of PFAS chemicals are also present in wastewater, fertilizers made from biosolids can have higher levels of these chemicals too. According to local officials in Johnson County (south of Fort Worth), the use of these fertilizers has led to illnesses and deaths in livestock. HB 1674 would have set limits on the amounts of certain PFAS chemicals that could remain in biosolid fertilizer, and would have established criminal penalties for making, distributing, and selling fertilizer with PFAS amounts above these limits. HB 1674 was authored by Rep. Helen Kerwin, who represents Johnson County, and many of her constituents testified in a lengthy committee hearing in May.

SB 768 — This bill would have directed the University of Houston, TCEQ, and the Texas Railroad Commission to conduct a study on the effects of PFAS chemicals on public health.

SB 1586 — While most wastewater treatment facilities are built on site, some small developments install prefabricated treatment units known as package plants, which may not be maintained as well as larger plants. This bill would have required package plants to have adequate security and weatherization, as well as sufficient funding for maintenance.

SB 1911 — This bill would have discontinued new wastewater discharge permits on the state’s last remaining pristine streams, while allowing development to continue on these rivers and creeks with wastewater irrigation permits. You can read more about the bill in this SBCA Explainer and in this Texas Tribune article. SBCA has strongly supported earlier versions of the Pristine Streams proposal, including a 2021 bill and a 2022 petition filed with TCEQ, and we plan to keep working on it in the 2027 session.

SB 1954 — This was a great bill filed by Sen. Donna Campbell, and SBCA hopes to see it filed again. It would have allowed counties to set stricter development and land use rules for specially designated water quality protections areas, which could be in an aquifer recharge zone, karst limestone area, floodplain, or riparian area. SB 1954 would have allowed officials to regulate the height and size of buildings; the percentage of a lot that could be occupied; population density; and the location and use of buildings and land for commercial, industrial, residential, or other purposes. The need for expanded county authority is even greater in the wake of the devastating Fourth of July floods in the Hill Country.

LEGISLATIVE STAGES

Chamber #1

1. Bill is referred to a committee.

2. Bill is heard in a committee meeting.

3. Bill is approved in a committee vote.

4. Bill is passed in a chamber vote. The bill then goes to:

Chamber #2

5-8. Bill must repeat the same four stages. If the bill passes both chambers, it goes to the:

Governor

They can choose to sign a bill, veto it, or let it be filed as law without their signature.

Responses